By Anthony Aarons

(Los Angeles Daily Journal)

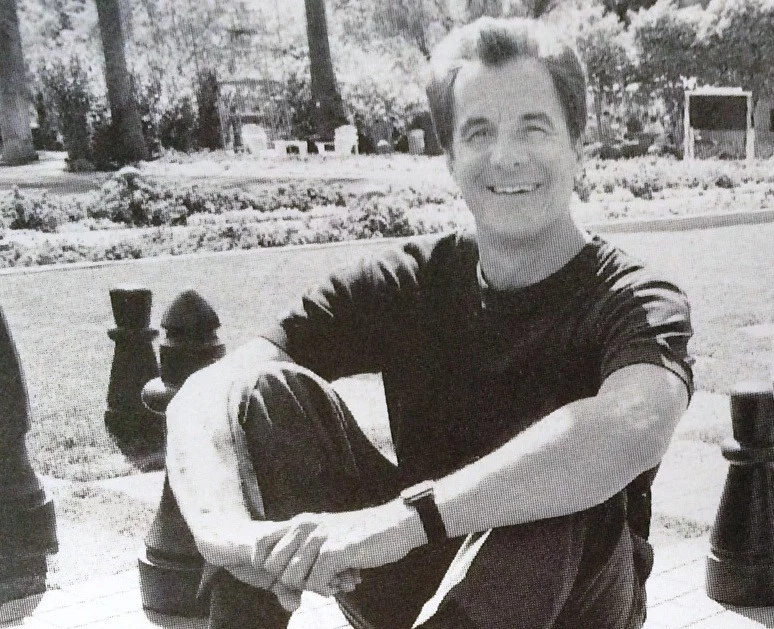

A California Attorney reached major-player status when he backed General Dynamics into a corner.

Twelve years ago Don Howarth left Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher with the hopes of leaving corporate defense work behind.

Today his own firm, Los Angeles' Howarth & Smith, still handles a fair amount of corporate defense work. Though his partner Suzelle Smith is currently defending Suzuki in a products liability case, the 20 lawyer firm has developed an eclectic list of clients including: the wife of the original Marlboro man in her suit against Phillip Morris and the estate of tobacco heiress Doris Duke. The firm also weighs in on a number of consumer-oriented class-action suits.

"These are the kinds of cases where you can feel like you are making a difference, where you are helping people," says Howarth, who handled his first plaintiff's case - a personal injury suit in which a boy fell off a ladder and became a paraplegic - the first year in his new firm.

Last summer, however, Howarth won a verdict that places him among the biggest names in California laintiffs lawyers when a Norwalk jury awarded two of his clients William Forti and Dolores Blanton, $107.4 million in a breach of contract suit against their former employer Falls Church, Va. --based General Dynamics. The suit was the largest verdict in California state courts in 1996, although it was reduced to $37.4 million by the trial judge. Although it was not a tragic personal injury suit or a tear-jerking insurance bad faith case, it was the kind of loyal employee vs. greedy corporate monster suit that wins over Jurors as well as headlines.

Don Howarth topped the list of lawyers securing the 10 biggest verdicts in California last year, netting their clients $285 million.

In 1990, Forti and Blanton, longtime General Dynamics' employees, were asked to leave their jobs at the company to start a new subsidiary for the company. The new company, to be called E-Metrics, was to develop a technology that would enable computers to recognize faces and that could be used as a security tool to identify criminals in a crowd. "It has many applications in airport security and other police work." Howarth says.

In exchange for starting the new company, Forti, Blanton and four other engineers, were promised equal shares of a 20 percent equity stake in the company. The plaintiffs did not receive a written contract, although Howarth says they received numerous verbal assurances of the agreement by General Dynamics Vice President Sterling Starr. In addition, they were told that it was too early to issue formal stock shares for the company.

Two years later E-Metrics was sold to Hughes as part of a $500 million package. When Forti and Blanton approached General Dynamics for their share of the proceeds from the sale of E-Metrics, they were told there was no such agreement.

General Dynamics essentially argued that when E-Metrics was sold to Hughes, the company had developed no products and recorded no sales.

Howarth contended that in addition to breach of contract, General Dynamics was guilty of fraud because it never intended to pay the "founders" of E-Metrics.

"In the sale to Hughes they never broke down the value of E-Metrics. I argued they did it on purpose to avoid paying any claims on the company," Howarth says.

Howarth says he was always comfortable with his clients' case. If Howarth was confident, General Dynamics was playing hardball on the eve of trial.

Howarth made a settlement demand of $1 million for each of the plaintiffs, while General Dynamics stood by an earlier offer of $100,000 each for Forti and Blanton. "That offer never changed during trial, even when I knew the jury was going with us," Howarth says.

The key moment of the trial came when General Dynamics' defense attorneys called Forti and Blanton's old boss, Starr, to the stand. Starr was under no legal duty to appear at the trial, he had retired and moved out of state, but the defense brought him to California as a major witness to rebut the plaintiffs' claims of an oral contract.

On cross, Starr's story fell apart as he contradicted his earlier deposition testimony. "He admitted he had adjusted his testimony to help the company," Howarth says. Howarth says that Starr's testimony could not be discounted in the jury's decision after only two days of deliberations - to award the plaintiffs combined compensatory damages of $7.4 million, their share of the value of 20 percent of E-Metrics. But, he says, Starr's testimony was even more important in the punitive damages phase of the trial. At this point, Howarth says, defense attorneys changed their strategy and accused Starr of wrongdoing.

"It was an incredible closing argument to cut the umbilical cord and blame it all on him. They didn't care who the jury blamed as long as it wasn't [General Dynamics]," Howarth says. Howarth's closing in the punitive damages phase of the trial took only 15 minutes, first to point out the hypocrisy of blaming Starr and then to explain the economic shortcomings of the $7.4 million compensatory award.

"All they had given them was what they were owed. At that point not paying [the plaintiffs] was a good business decision for General Dynamics. They had to punish them for refusing to honor the contract and trying to hide the value of the company," Howarth says.

The jury only took a few hours to return a punitive damages award of $100 million.

A 15-minute close might seem short, but Howarth purposely tried to keep everything brief during the three-week trial.

"We had enough material to make it last two months, but that just would have confused the jury," says Howarth who has three degrees from Harvard University, including his J.D., a B.A. and a masters in public policy. Although General Dynamics' defense attorneys did not return calls for comment, a press release issued after the trial asserted that E-Metrics had no value.

"In fact, General Dynamics told E-Metrics employees, in writing, that the E-Metrics board would decide upon equity interest once outside investors were obtained. When E-Metrics failed to attract outside investors, General Dynamics discontinued the business," the July press release stated. "General Dynamics can hardly be expected to have shared with employees the fruits of a business that never made a dime."

Judge Chris Conway reduced the punitive damages award to $30 million. While it might seem the judge reduced the punitive damages because of the excessive ratio to the compensatory damages, Howarth says that was not the case. In the first place, he says, the $100 million punitive is fair when compared to the value of both General Dynamics and E-Metrics. More importantly, in the judge's opinion, the punitives were cut to allow some damages to remain in the event the four engineers-the other "founders" along with Forti and Blanton-file suit against General Dynamics.

"It was a very reasoned opinion," Howarth says. Howarth now represents the engineers and is considering what action, if any, is still available for them. General Dynamics is appealing the verdict on numerous grounds, including the statute of frauds and the statute of limitations. The statute of frauds dictates when an oral contract is valid-and Howarth admits this could be the defense's strongest argument, but the trial judge ruled against two motions on that claim during trial. Although Howarth says that settlement negotiations have not been promising, General Dynamics General Counsel, says that a settlement could be near.

"We've had substantial discussions" to try and settle the case, said Ned Bruntrager, general counsel of General Dynamics: "The true nature of those discussions is confidential, but the fact is they were being held at the direction of the Court of Appeals. We've not inked a final agreement. It's technically correct that there is no final agreement." But, he added, "I would be surprised if that case is not settled shortly."

As the lead attorney in the biggest verdict of 1996, Don Howarth of Howarth & Smith took on and beat General Dynamics. A jury's $107 million award in the breach of contract lawsuit tops our annual list of the 10 largest verdicts, which netted their clients a total of $285 million. Today's issue of California Law Business also examines the downward trend in dollar totals.

CHECKMATE!